COVID-19 may have led to a decrease in worldwide inequality

Prevailing wisdom says that income inequality has increased due to COVID-19. But has it? A new working paper by Angus Deaton argues exactly the opposite: inequality has actually decreased. But only if one takes China out of the picture.

One of the greatest tragedies of COVID-19 has been the loss of life and livelihood amongst the poorest of the poor. Multiple countries have seen the breakdown of social security systems, deaths in the hundreds if not thousands, and job losses across the board. The question of lives vs livelihood has played out in different ways across the world. From the chaotic mismanagement in America to Taiwan's deft handling, though, conventional wisdom has it that the poor have borne a disproportionate brunt of the pandemic.

A recent NBER working paper by Angus Deaton challenges that notion. He argues that global inequality hasn't increased, but decreased due to the pandemic. He sets his argument out using three premises:

The number of deaths per capita has been higher in richer countries

This statement forms the crux of his paper. Conventional wisdom would have one believe that richer countries would tend to do better in pandemic prevention and control. And typically, that tends to be true. Health outcomes are better in richer countries with more developed health systems. A comprehensive study published by Johns Hopkins, the Nuclear Threat Initiative, and the Economist intelligence Unit about global health security created a set of global health indices which measure country capacity in 6 dimensions using 140 questions. Four of these dimensions are:

Prevention of the emergence and release of pathogens

Early detection and reporting for epidemics of potential international concern

Rapid response and mitigation of the spread of an epidemic

Sufficiency and robustness of the health system to treat the sick and protect health workers

Countries which tend to do well in each of these dimensions tend to be richer and wealthier. However, richer and wealthier countries also have a high mortality rate as a result of COVID-19.

So in essence, what this tells us is that countries with better health systems as measured by the Global Health Security Index have tended to do worse than countries with worse health systems, a fairly counter-intuitive result.

The author does make it clear though, that this is not his last word on this assertion. The pandemic isn't yet done devastating our species. Tanzania and Burundi have extremely low death rates: to assume that their data collection has been perfect would be wrong. Vaccines have not yet had any chance to affect deaths yet as well. Rich countries, with better health systems and more efficient systems may yet outpace poor countries in vaccine distribution. Poor countries also have the edge over rich countries in terms of demographics and weather. Poor countries also tend to be warmer: more work is done outside as compared to rich countries. In addition, countries like Taiwan, South korea, China, and many in Africa also have institutional experience of combating SARS and other infectious epidemics: experience which rich countries lack.

The author does not wish to disentangle the relationship between all these factors. At this point, all that needs to be asserted is that there is a positive relationship between number of deaths per capita and per capita income.

There is a negative relationship between predicted GDP growth and deaths per capita

The second argument comes from a straightforward look at the figures published by the IMF and the World Bank and it gives us an easy assertion. If a country has more deaths per capita, then the decrease in its GDP will be greater.

The relationship here is a lot clearer than that for deaths per capita vs income. China and India both are outliers: China has had far fewer deaths than its population would indicate, and India has had greater.

This brings the relationship between lives and economics starkly into the picture. The perceived relationship was one of trade-off between economics and saving lives. But a look at the data shows us that saving lives and economics were inexplicably linked. While this might seem somewhat obvious in retrospect, it was not obvious when lockdowns were being implemented that they would be anything but a good idea.

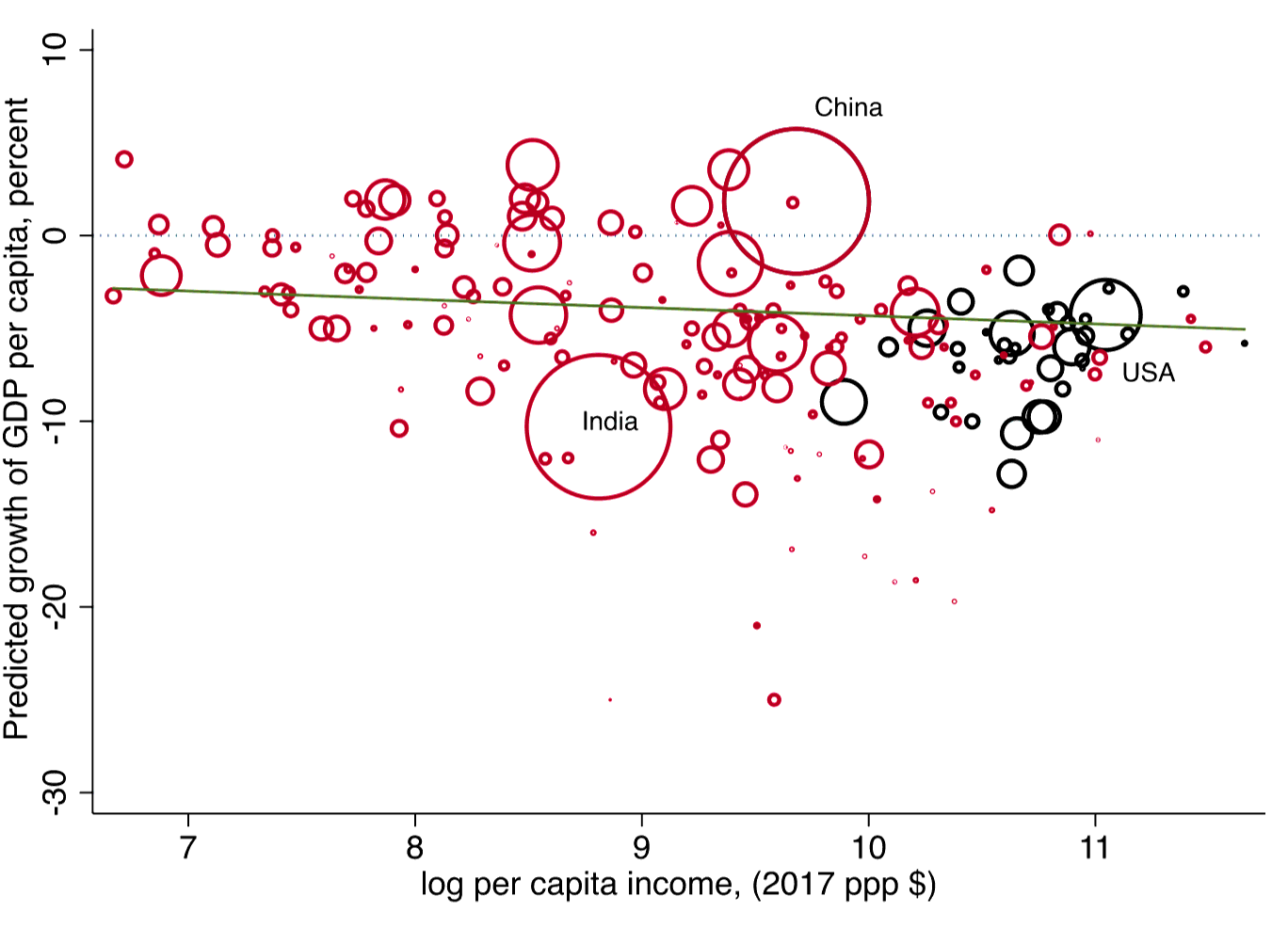

There is a negative relationship between per capita income and predicted GDP growth

The last assertion in this argument shows that richer countries grew slower. The relationship is fairly slight, but it does exist.

While the relationship isn't as stark as the one between deaths per capita and GDP growth, one can still see where it's going.

Income inequality has decreased across the world. If you take out China.

And this brings us to the final statement. A careful look at the data actually shows that income inequality has fallen. To explain what one means by that, one needs to understand how income inequality may be measured. From the horse's mouth itself:

My results concern two distinct measures of international income inequality, the dispersion of per capita income between countries, with each country as a unit of observation, and the dispersion of per capita income between countries, but where each country is weighted by population. Milanovic (2011, Chapters 1 and 2) has usefully labeled these inequality measures as Concept 1 and Concept 2 respectively. Concept 1 treats each country as an individual and calculates inequality between those individuals. Concept 2 pretends that each person in the world has their country’s per capita income, and then calculates inequality among all these persons. Both Concept 1 and Concept 2 are between country measures and both ignore within country inequality.

The data for plotting this graph come from the World Economic Outlook 2020 (for the solid lines) and 2019 (for the dashed lines). The 2019 document also has pre-pandemic predictions for 2020, which the graph shows. It shows the standard deviation in log per-capita income over different years. If one looks closely, one can see a dip at around 2008 during the Great Recession in all three sets of time series.

The lines on the top are population unweighted data (concept 1). The lines in the middle are weighted but excluding China, and the lines of the bottom are weighted and include China. Income inequality has been falling over the years as China and India pull themselves out of poverty. However, there is a clean break in 2020 when one looks at population-weighted data. Inequality actually did rise in the world for the first time in many many years.

The reason behind this is entirely China, which pulled itself out of the pandemic much better than had been expected. As the author says, the reason why this uptick has happened is because it has pushed 1.4 billion Chinese people ahead of 1.4 billion Indian people. Since more people are now poorer than the Chinese than are richer than them, the more China pulls away from the mean, the more inequality grows.

Limitations

However, this study ought not to be the last word on this topic. It totally ignores the pain and suffering which many people have gone through, most of which has been in poorer countries. It also does not account for the number of people who have been pushed back into poverty in poorer countries as their incomes have dropped. Tales of dropping or rising inequality do not change their predicament. It also does not look at the role of institutional knowledge and strength, or for that matter, trust in the government.

In addition, the statement of "richer countries have suffered more than poorer countries" ought to be obvious: richer countries have more to lose. However, it does challenge the methodology used to assess health system readiness for epidemics. The six dimensions used to assess readiness were obviously not enough, else there would be no divide between facts on the ground and theory.

Finally, there might be other types of inequality which have grown during this time: access to opportunities, jobs, medicines, and a better future, for instance. Relegating them to a distant last in pursuit of economic growth ought not to be the driving ethos of any modern society. Even if one looks at economic growth, this study does not look at within-country inequality, which may have actually increased during this pandemic as resources concentrate in the hands of those who already have a lot.